Easter

Modern-day Easter is derived from two ancient traditions: one Judeo-Christian and the other Pagan. Both Christians and Pagans have celebrated death and resurrection themes following the Spring Equinox for millennia.

Ancient civilizations' culture and livelihood centered around weather and the seasons. Fall and winter marked harsh times and the death or hibernation of crops and food sources, while Spring was a time of rebirth. As a result, the changing of the seasons were marked with a wide variety of rituals.

Most religious historians believe that many elements of the Christian observance of Easter were derived from earlier Pagan celebrations.

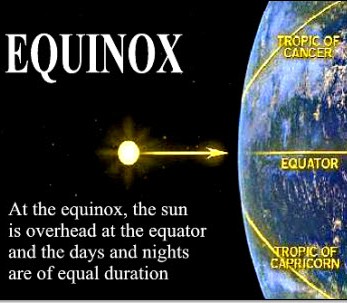

The equinox occurs each year on March 20, 21 or 22. Both Neopagans and Christians continue to celebrate religious rituals linked to the equinox in the present day. Wiccans and other Neopagans usually hold their celebrations on the day or eve of the equinox. Western Christians wait until the Sunday on or after the next full moon. The Eastern Orthodox churches follow a different calculation; their celebration is often many weeks after the date selected by the Western churches.

Contents |

Historicity of the Easter celebrations

If Easter isn't really about Jesus, then what is it about? Today, we see a secular culture celebrating the spring equinox, whilst religious culture celebrates the resurrection. However, early Christianity made a pragmatic acceptance of ancient pagan practices, most of which we enjoy today at Easter. The general symbolic story of the death of the son (sun) on a cross (the constellation of the Southern Cross) and his rebirth, overcoming the powers of darkness, was a well worn story in the ancient world. There were plenty of parallel, rival resurrected saviours too.

The Sumerian goddess Inanna, or Ishtar, was hung naked on a stake, and was subsequently resurrected and ascended from the underworld. One of the oldest resurrection myths is Egyptian Horus. Born on 25 December, Horus and his damaged eye became symbols of life and rebirth. Mithras was born on what we now call Christmas day, and his followers celebrated the spring equinox. Even as late as the 4th century AD, the sol invictus, associated with Mithras, was the last great pagan cult the church had to overcome. Dionysus was a divine child, resurrected by his grandmother. Dionysus also brought his mum, Semele, back to life.

In an ironic twist, the Cybele cult flourished on today's Vatican Hill. Cybele's lover Attis, was born of a virgin, died and was reborn annually. This spring festival began as a day of blood on Black Friday, rising to a crescendo after three days, in rejoicing over the resurrection. There was violent conflict on Vatican Hill in the early days of Christianity between the Jesus worshippers and pagans who quarrelled over whose God was the true, and whose the imitation. What is interesting to note here is that in the ancient world, wherever you had popular resurrected god myths, Christianity found lots of converts. So, eventually Christianity came to an accommodation with the pagan Spring festival. Although we see no celebration of Easter in the New Testament, early church fathers celebrated it, and today many churches are offering "sunrise services" at Easter – an obvious pagan solar celebration. The date of Easter is not fixed, but instead is governed by the phases of the moon – how pagan is that?

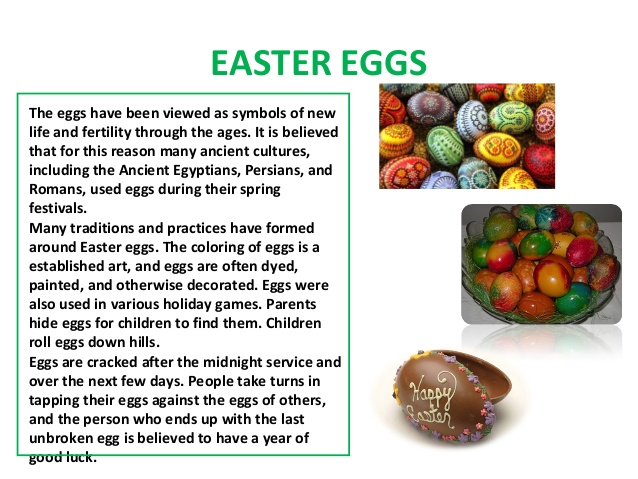

All the fun things about Easter are pagan. Bunnies are a leftover from the pagan festival of Eostre, a great northern goddess whose symbol was a rabbit or hare. Exchange of eggs is an ancient custom, celebrated by many cultures. Hot cross buns are very ancient too. In the Old Testament we see the Israelites baking sweet buns for an idol, and religious leaders trying to put a stop to it. The early church clergy also tried to put a stop to sacred cakes being baked at Easter. In the end, in the face of defiant cake-baking pagan women, they gave up and blessed the cake instead.

Easter is essentially a pagan festival which is celebrated with cards, gifts and novelty Easter products, because it's fun and the ancient symbolism still works. It's always struck me that the power of nature and the longer days are often most felt in modern towns and cities, where we set off to work without putting on our car headlights and when our alarm clock goes off in the mornings, the streetlights outside are not still on because of the darkness.[1]Origin of the name "Easter"

The name "Easter" originated with the names of an ancient Goddess and God. The Venerable Bede, (672-735 CE.) a Christian scholar, first asserted in his book, De Ratione Temporum that Easter was named after Eostre (a.k.a. Eastre). She was the Great Mother Goddess of the Saxon people in Northern Europe. Similarly, the "Teutonic dawn goddess of fertility [was] known variously as Ostare, Ostara, Ostern, Eostra, Eostre, Eostur, Eastra, Eastur, Austron and Ausos."[2] Her name was derived from the ancient word for spring: "eastre." Similar Goddesses were known by other names in ancient cultures around the Mediterranean, and were celebrated in the springtime. Some were:

- Aphrodite from ancient Cyprus

- Ashtoreth from ancient Israel

- Astarté from ancient Greece

- Demeter from Mycenae

- Hathor from ancient Egypt

- Ishtar from Assyria

- Kali, from India

- Ostara a Norse Goddess of fertility.

An alternative explanation has been suggested. The name given by the Frankish church to Jesus' resurrection festival included the Latin word "alba" which means "white." (This was a reference to the white robes that were worn during the festival.) "Alba" also has a second meaning: "sunrise." When the name of the festival was translated into German, the "sunrise" meaning was selected in error. This became "ostern" in German. Ostern has been proposed as the origin of the word "Easter".[3]

Pagan origins of Easter

Many, perhaps most, Pagan religions in the Mediterranean area had a major seasonal day of religious celebration at or following the Spring Equinox. Cybele, the Phrygian fertility goddess, had a fictional consort who was believed to have been born via a virgin birth. He was Attis, who was believed to have died and been resurrected each year during the period MAR-22 to MAR-25. "About 200 B.C. mystery cults began to appear in Rome just as they had earlier in Greece. Most notable was the Cybele cult centered on Vatican hill ...Associated with the Cybele cult was that of her lover, Attis (the older Tammuz, Osiris, Dionysus, or Orpheus under a new name). He was a god of ever-reviving vegetation. Born of a virgin, he died and was reborn annually. The festival began as a day of blood on Black Friday and culminated after three days in a day of rejoicing over the resurrection."[4]

Wherever Christian worship of Jesus and Pagan worship of Attis were active in the same geographical area in ancient times, Christians "used to celebrate the death and resurrection of Jesus on the same date; and pagans and Christians used to quarrel bitterly about which of their gods was the true prototype and which the imitation."

Many religious historians believe that the death and resurrection legends were first associated with Attis, many centuries before the birth of Jesus. They were simply grafted onto stories of Jesus' life in order to make Christian theology more acceptable to Pagans. Others suggest that many of the events in Jesus' life that were recorded in the gospels were lifted from the life of Krishna, the second person of the Hindu Trinity. Ancient Christians had an alternative explanation; they claimed that Satan had created counterfeit deities in advance of the coming of Christ in order to confuse humanity.[5] Modern-day Christians generally regard the Attis legend as being a Pagan myth of little value. They regard Jesus' death and resurrection account as being true, and unrelated to the earlier tradition.

Wiccans and other modern-day Neopagans continue to celebrate the Spring Equinox as one of their 8 yearly Sabbats (holy days of celebration). Near the Mediterranean, this is a time of sprouting of the summer's crop; farther north, it is the time for seeding. Their rituals at the Spring Equinox are related primarily to the fertility of the crops and to the balance of the day and night times. Where Wiccans can safely celebrate the Sabbat out of doors without threat of religious persecution, they often incorporate a bonfire into their rituals, jumping over the dying embers is believed to assure fertility of people and crops.

There are two popular beliefs about the origin of the English word "Sunday."

- It is derived from the name of the Scandinavian sun Goddess Sunna (a.k.a. Sunne, Frau Sonne).[6]

- It is derived from "Sol," the Roman God of the Sun." Their phrase "Dies Solis" means "day of the Sun." The Christian saint Jerome (d. 420) commented "If it is called the day of the sun by the pagans, we willingly accept this name, for on this day the Light of the world arose, on this day the Sun of Justice shone forth."[7]

Origins of Easter traditions

So how did Pagan symbols become entwined with the Christian holiday of Easter? When the Christian Church was first trying to convert the Pagans to Christianity, they ran into problems. The Pagans did not want to give up their festivals as well as their gods, so the Christians simply incorporated some Pagan practices into the Christian festivals. This made Christianity more palatable to the Pagan people who were reluctant to give up their festivals for the more sombre Christian practices.

Rabbits and eggs?

1500 years or so after the incorporation, the Germans had a tradition of their own. A rabbit, called Oschter Haws, layed colored eggs in nests and delighted children who then got to 'find' the eggs. This was introduced to America by German settlers in Pennsylvania.

In these modern times, you can buy chocolate representations of rabbits and eggs. While some still hold to old traditions and color eggs by hand, those who do not have the time or inclination can simply go to the store and buy candy, pre-dyed eggs, and other goodies. Ducks, chickens and rabbits are also highly popular choices for childrens' gift baskets on Easter morning.

References

- . Heather McDougall, The Guardian, https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/belief/2010/apr/03/easter-pagan-symbolism

- . Larry Boemler "Asherah and Easter," Biblical Archaeology Review, Vol. 18, Number 3, 1992-May/June

- . Wisconsin Evangelical Lutheran Synod Q & A Set 15, "Why do we celebrate a festival called Easter?" at: http://www.wels.net/sab/text/qa/qa15.html

- . Gerald L. Berry, "Religions of the World," Barns & Noble, (1956).

- . J Farrar & S. Farrar, "Eight Sabbats for Witches," Phoenix, Custer, WA, (1988).

- . Sunna,"TeenWitch at: http://www.teenwitch.com; "Dies Solis and other Latin Names for the Days of the Week," Logo Files, at: http://www.logofiles.com/

- . Sunday Observance," Latin Mass News, at: http://www.unavoceca.org/

This site costs a lot of money in bandwidth and resources. We are glad to bring it to you free, but would you consider helping support our site by making a donation? Any amount would go a long way towards helping us continue to provide this useful service to the community.

Click on the Paypal button below to donate. Your support is most appreciated! |

|---|