Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein: on religion

I believe in Spinoza's God who reveals Himself in the orderly harmony of what exists, not in a God who concerns himself with fates and actions of human beings.

- The quotation above may be Einstein's most familiar statement of his beliefs. These words are frequently quoted, but a citation is seldom given. The quotation can be found in Albert Einstein: Philosopher-Scientist edited by Paul Arthur Schilpp (The Open Court Publishing Co., La Salle, Illinois, Third Edition, 1970) pp. 659 - 660. There the source is given as the New York Times, 25 April 1929, p. 60, col. 4. Ronald W. Clark (pp. 413-414) gives a detailed account of the origin of Einstein's statement.

Christianity and Judaism

If one purges the Judaism of the Prophets and Christianity as Jesus taught it of all subsequent additions, especially those of the priests, one is left with a teaching which is capable of curing all the social ills of humanity.

It is the duty of every man of good will to strive steadfastly in his own little world to make this teaching of pure humanity a living force, so far as he can. If he makes an honest attempt in this direction without being crushed and trampled under foot by his contemporaries, he may consider himself and the community to which he belongs lucky.[1]

Greater Things Than Jesus

It is quite possible that we can do greater things than Jesus, for what is written in the Bible about him is poetically embellished.[2]

The Kingdom of God

One has a feeling that one has a kind of home in this timeless community of human beings that strive for truth. … I have always believed that Jesus meant by the Kingdom of God the small group scattered all through time of intellectually and ethically valuable people.[3]

About Converting to Christianity

A Catholic science student, concerned for Einstein's soul, once wrote to Einstein, begging him to pray to Christ, the Virgin Mary, and to see a Catholic priest immediately. What follows is part of Einstein's reply.

If I would follow your advice and Jesus could perceive it, he, as a Jewish teacher, surely would not approve of such behavior.[4]

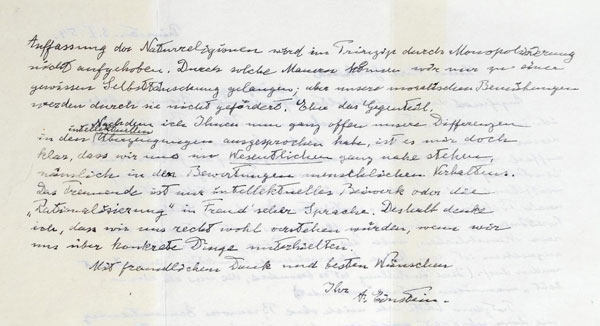

Einstein's letter calling belief in God "childish"

| Albert Einstein described belief in God as "childish superstition" and said Jews were not the chosen people, in a letter to be sold in London the week of May 12, 2008. The father of relativity, whose previously known views on religion have been more ambivalent and fuelled much discussion, made the comments in response to a philosopher in 1954. As a Jew himself, Einstein said he had a great affinity with Jewish people but said they "have no different quality for me than all other people". "The word God is for me nothing more than the expression and product of human weaknesses, the Bible a collection of honourable, but still primitive legends which are nevertheless pretty childish. "No interpretation no matter how subtle can (for me) change this," he wrote in the letter written on January 3, 1954 to the philosopher Eric Gutkind, cited by The Guardian newspaper. The German-language letter is being sold Thursday by Bloomsbury Auctions in Mayfair after being in a private collection for more than 50 years, said the auction house's managing director Rupert Powell. In it, the renowned scientist, who declined an invitation to become Israel's second president, rejected the idea that the Jews are God's chosen people. "For me the Jewish religion like all others is an incarnation of the most childish superstitions," he said. "And the Jewish people to whom I gladly belong and with whose mentality I have a deep affinity have no different quality for me than all other people." And he added: "As far as my experience goes, they are no better than other human groups, although they are protected from the worst cancers by a lack of power. Otherwise I cannot see anything 'chosen' about them." Previously the great scientist's comments on religion -- such as "Science without religion is lame, religion without science is blind" -- have been the subject of much debate, used notably to back up arguments in favour of faith. Powell said the letter being sold this week gave a clear reflection of Einstein's real thoughts on the subject. "He's fairly unequivocal as to what he's saying. There's no beating about the bush." [5] |

|---|

Einstein's youth: becoming a freethinker and a scientist

From Einstein's "Autobiographical Notes", pp3-5:

"When I was a fairly precocious young man I became thoroughly impressed with the futility of the hopes and strivings that chase most men restlessly through life. Moreover, I soon discovered the cruelty of that chase, which in those years was much more carefully covered up by hypocrisy and glittering words than is the case today. By the mere existence of his stomach everyone was condemned to participate in that chase. The stomach might well be satisfied by such participation, but not man insofar as he is a thinking and feeling being.Young EinsteinAs the first way out there was religion, which is implanted into every child by way of the traditional education-machine. Thus I came - though the child of entirely irreligious (Jewish) parents - to a deep religiousness, which, however, reached an abrupt end at the age of twelve. Through the reading of popular scientific books I soon reached the conviction that much in the stories of the Bible could not be true. The consequence was a positively fanatic orgy of freethinking coupled with the impression that youth is intentionally being deceived by the state through lies; it was a crushing impression. Mistrust of every kind of authority grew out of this experience, a skeptical attitude toward the convictions that were alive in any specific social environment — an attitude that has never again left me, even though, later on, it has been tempered by a better insight into the causal connections. It is quite clear to me that the religious paradise of youth, which was thus lost, was a first attempt to free myself from the chains of the "merely personal," from an existence dominated by wishes, hopes, and primitive feelings. Out yonder there was this huge world, which exists independently of us human beings and which stands before us like a great, eternal riddle, at least partially accessible to our inspection and thinking. The contemplation of this world beckoned as a liberation, and I soon noticed that many a man whom I had learned to esteem and to admire had found inner freedom and security in its pursuit. The mental grasp of this extra-personal world within the frame of our capabilities presented itself to my mind, half consciously, half unconsciously, as a supreme goal. Similarly motivated men of the present and of the past, as well as the insights they had achieved, were the friends who could not be lost. The road to this paradise was not as comfortable and alluring as the road to the religious paradise; but it has shown itself reliable, and I have never regretted having chosen it." |

|---|

Einstein interview about religion

The following comes from "What Life Means to Einstein: An Interview by George Sylvester Viereck,"The Saturday Evening Post, Oct. 26, 1929, p. 17. The questions are posed by Viereck; the reply to each is by Einstein. Since the interview was conducted in Berlin and both Viereck and Einstein had German as their mother tongue, the interview was likely conducted in German and then translated into English by Viereck.

Some portions of this interview might seem questionable, but this portion of the interview was explicitly confirmed by Einstein. When asked about a clipping from a magazine article (likely the Saturday Evening Post) reporting Einstein's comments on Christianity taken down by Viereck, Einstein carefully read the clipping and replied, "That is what I believe."[6]

"To what extent are you influenced by Christianity?"

"As a child, I received instruction both in the Bible and in the Talmud. I am a Jew, but I am enthralled by the luminous figure of the Nazarene."

"Have you read Emil Ludwig's book on Jesus?

"Emil Ludwig's Jesus," replied Einstein, "is shallow. Jesus is too colossal for the pen of phrasemongers, however artful. No man can dispose of Christianity with a bon mot."

"You accept the historical existence of Jesus?"

"Unquestionably. No one can read the Gospels without feeling the actual presence of Jesus. His personality pulsates in every word. No myth is filled with such life. How different, for instance, is the impression which we receive from an account of legendary heroes of antiquity like Theseus. Theseus and other heroes of his type lack the authentic vitality of Jesus."

"Ludwig Lewisohn, in one of his recent books, claims that many of the sayings of Jesus paraphrase the sayings of other prophets."

"No man," Einstein replied, "can deny the fact that Jesus existed, nor that his sayings are beautiful. Even if some them have been said before, no one has expressed them so divinely as he." On Buddha, Moses, and Jesus

Our time is distinguishedby wonderful achievements in the fields of scientific understanding and the technical application of those insights. Who would not be cheered by this? But let us not forget that knowledge and skills alone cannot lead humanity to a happy and dignified life. Humanity has every reason to place the proclaimers of high moral standards and values above the discoverers of objective truth. What humanity owes to personalities like Buddha, Moses, and Jesus ranks for me higher than all the achievements of the enquiring and constructive mind.

What these blessed men have given us we must guard and try to keep alive with all our strength if humanity is not to lose its dignity, the security of its existence, and its joy in living.[7]

Answersingenesis recognizes the fallacious argument

Some people might cite Einstein as a believer of god and use him as an argument from authority to further support their views (that a belief in god or religion is good). However even Answers In Genesis recognizes this as a fallacious argument and writes that Einstein believed no such thing, one of the many arguments that the site advises creationists not to use.

AiG also has two articles on the issue:

References

- . From Einstein's book The World as I See It (Philosophical Library, New York, 1949) pp. 111-112

- . From W. I. Hermanns "A Talk with Einstein," October 1943, Einstein Archive 55-285

- . From Goldman, p. 98.

- . Goldman, p. 88.

- . letter written on January 3, 1954 to the philosopher Eric Gutkind, cited by The Guardian newspaper.

- . Brian, Denis, Einstein — A Life (John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York, 1996) pp. 277 - 278.

- . Goldman, Robert N., Einstein's God—Albert Einstein's Quest as a Scientist and as a Jew to Replace a Forsaken God (Joyce Aronson Inc.; Northvale, New Jersy; 1997). p.88

This site costs a lot of money in bandwidth and resources. We are glad to bring it to you free, but would you consider helping support our site by making a donation? Any amount would go a long way towards helping us continue to provide this useful service to the community.

Click on the Paypal button below to donate. Your support is most appreciated! |

|---|